If the Price of a Good Rises, What Are People Likely to Do?

5.1 The Price Elasticity of Need

Learning Objectives

- Explain the concept of price elasticity of demand and its adding.

- Explain what it ways for demand to be price inelastic, unit of measurement price elastic, price rubberband, perfectly cost inelastic, and perfectly price elastic.

- Explain how and why the value of the toll elasticity of demand changes along a linear demand curve.

- Understand the relationship between total revenue and price elasticity of demand.

- Discuss the determinants of toll elasticity of demand.

We know from the law of need how the quantity demanded will respond to a price change: it volition alter in the opposite direction. But how much volition information technology change? It seems reasonable to expect, for case, that a 10% change in the price charged for a visit to the physician would yield a different percentage change in quantity demanded than a 10% change in the price of a Ford Mustang. Just how much is this difference?

To show how responsive quantity demanded is to a change in cost, we apply the concept of elasticity. The price elasticity of demand for a practiced or service, e D, is the percentage change in quantity demanded of a particular good or service divided by the percent change in the price of that good or service, all other things unchanged. Thus we can write

Equation 5.ii

[latex]e_D = \frac{\% \ modify \ in \ quantity \ demanded}{\% \ alter \ in \ price}[/latex]

Considering the toll elasticity of need shows the responsiveness of quantity demanded to a cost modify, assuming that other factors that influence demand are unchanged, it reflects movements forth a need bend. With a downward-sloping need curve, cost and quantity demanded move in opposite directions, and then the price elasticity of demand is always negative. A positive pct change in price implies a negative percentage modify in quantity demanded, and vice versa. Sometimes you will run across the accented value of the price elasticity mensurate reported. In essence, the minus sign is ignored because it is expected that there will exist a negative (inverse) relationship betwixt quantity demanded and toll. In this text, however, nosotros will retain the minus sign in reporting price elasticity of demand and volition say "the absolute value of the price elasticity of need" when that is what we are describing.

Heads Upwardly!

Be careful not to confuse elasticity with slope. The gradient of a line is the modify in the value of the variable on the vertical centrality divided past the modify in the value of the variable on the horizontal axis between two points. Elasticity is the ratio of the percentage changes. The slope of a need curve, for example, is the ratio of the change in price to the alter in quantity between two points on the bend. The price elasticity of demand is the ratio of the percentage alter in quantity to the per centum modify in toll. As nosotros volition run across, when computing elasticity at different points on a linear demand curve, the slope is constant—that is, it does non change—but the value for elasticity will change.

Computing the Cost Elasticity of Demand

Finding the price elasticity of demand requires that nosotros first compute percent changes in price and in quantity demanded. We summate those changes between two points on a demand curve.

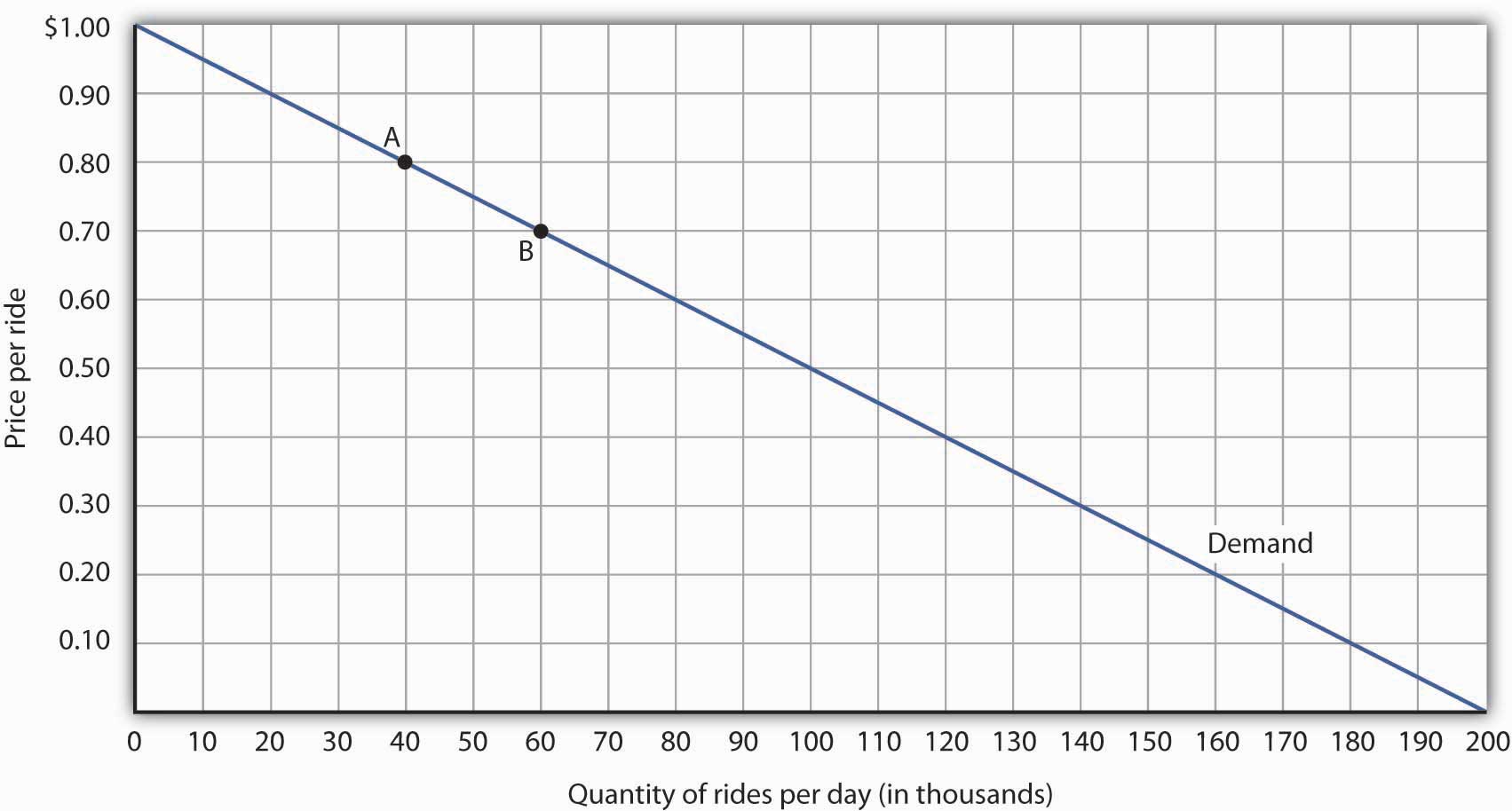

Figure five.1 "Responsiveness and Demand" shows a particular demand curve, a linear demand curve for public transit rides. Suppose the initial price is $0.fourscore, and the quantity demanded is 40,000 rides per day; we are at point A on the curve. At present suppose the toll falls to $0.seventy, and nosotros want to study the responsiveness of the quantity demanded. We come across that at the new toll, the quantity demanded rises to 60,000 rides per twenty-four hour period (point B). To compute the elasticity, nosotros need to compute the percentage changes in price and in quantity demanded between points A and B.

Effigy 5.1 Responsiveness and Demand

The demand curve shows how changes in price lead to changes in the quantity demanded. A motility from signal A to indicate B shows that a $0.ten reduction in price increases the number of rides per day past 20,000. A movement from B to A is a $0.10 increase in price, which reduces quantity demanded past 20,000 rides per day.

We measure out the per centum alter between two points as the change in the variable divided by the average value of the variable between the two points. Thus, the per centum change in quantity betwixt points A and B in Effigy 5.one "Responsiveness and Demand" is computed relative to the average of the quantity values at points A and B: (60,000 + 40,000)/2 = 50,000. The per centum alter in quantity, then, is 20,000/50,000, or forty%. As well, the per centum change in price between points A and B is based on the boilerplate of the ii prices: ($0.lxxx + $0.70)/2 = $0.75, and and then nosotros have a percentage modify of −0.10/0.75, or −thirteen.33%. The cost elasticity of demand between points A and B is thus 40%/(−13.33%) = −3.00.

This measure of elasticity, which is based on per centum changes relative to the average value of each variable betwixt 2 points, is called arc elasticity. The arc elasticity method has the advantage that it yields the same elasticity whether we go from point A to point B or from bespeak B to point A. It is the method we shall use to compute elasticity.

For the arc elasticity method, we calculate the cost elasticity of demand using the average value of cost, $$ \bar{P} $$ , and the average value of quantity demanded, $$ \bar{Q} $$. We shall apply the Greek letter of the alphabet Δ to mean "change in," and then the change in quantity between two points is ΔQ and the modify in toll is ΔP. At present nosotros tin write the formula for the price elasticity of demand as

Equation 5.3

[latex]\displaystyle e_D = \frac{\Delta Q / \bar{Q}}{\Delta P / \bar{P}}[/latex]

The toll elasticity of demand between points A and B is thus:

[latex]e_D = \frac{\frac{20,000}{(twoscore,000+60,000)/two}}{\frac{- \$ 0.x}{( \$ 0.lxxx + \$ 0.seventy)/2}} = \frac{xl \% }{-xiii.33 \% } = -3.00[/latex]

With the arc elasticity formula, the elasticity is the same whether we movement from point A to point B or from betoken B to point A. If we showtime at point B and motion to point A, we have:

[latex]e_D = \frac{\frac{-20,000}{(sixty,000+40,000)/two}}{\frac{ \$ 0.ten}{( \$ 0.80 + \$ 0.lxx)/2}} = \frac{-40 \% }{13.33 \% } = -three.00[/latex]

The arc elasticity method gives united states an approximate of elasticity. It gives the value of elasticity at the midpoint over a range of alter, such equally the movement betwixt points A and B. For a precise computation of elasticity, we would need to consider the response of a dependent variable to an extremely small modify in an contained variable. The fact that arc elasticities are approximate suggests an important practical rule in calculating arc elasticities: we should consider simply small changes in contained variables. We cannot apply the concept of arc elasticity to big changes.

Another argument for considering only small-scale changes in calculating price elasticities of demand will become evident in the next section. We volition investigate what happens to price elasticities as nosotros move from one point to another forth a linear demand curve.

Heads Up!

Notice that in the arc elasticity formula, the method for computing a percentage change differs from the standard method with which you may exist familiar. That method measures the percentage modify in a variable relative to its original value. For example, using the standard method, when we go from point A to point B, we would compute the percentage modify in quantity every bit 20,000/xl,000 = 50%. The percent modify in toll would be −$0.10/$0.80 = −12.5%. The price elasticity of demand would then exist 50%/(−12.five%) = −4.00. Going from point B to signal A, yet, would yield a different elasticity. The pct change in quantity would be −xx,000/60,000, or −33.33%. The pct change in cost would exist $0.ten/$0.70 = 14.29%. The toll elasticity of demand would thus be −33.33%/14.29% = −2.33. By using the boilerplate quantity and average price to calculate percentage changes, the arc elasticity approach avoids the necessity to specify the management of the change and, thereby, gives us the aforementioned answer whether we get from A to B or from B to A.

Price Elasticities Along a Linear Demand Bend

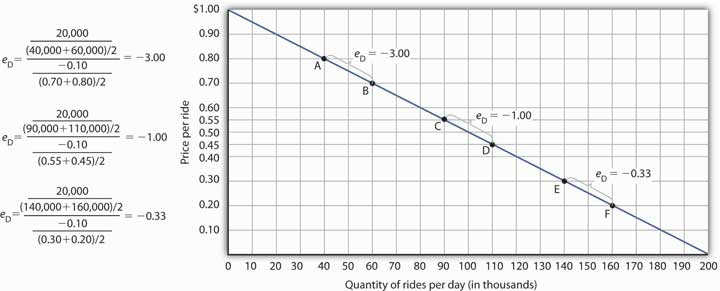

What happens to the cost elasticity of demand when we travel forth the demand curve? The respond depends on the nature of the demand curve itself. On a linear demand curve, such as the 1 in Figure 5.2 "Price Elasticities of Demand for a Linear Demand Curve", elasticity becomes smaller (in accented value) every bit we travel downwardly and to the right.

Effigy 5.2 Price Elasticities of Demand for a Linear Need Curve

The price elasticity of demand varies between different pairs of points forth a linear demand bend. The lower the cost and the greater the quantity demanded, the lower the absolute value of the price elasticity of need.

Effigy five.2 "Price Elasticities of Demand for a Linear Demand Curve" shows the aforementioned demand curve nosotros saw in Figure 5.1 "Responsiveness and Need". We take already calculated the toll elasticity of demand between points A and B; it equals −iii.00. Notice, still, that when we apply the aforementioned method to compute the toll elasticity of demand between other sets of points, our answer varies. For each of the pairs of points shown, the changes in cost and quantity demanded are the same (a $0.10 subtract in cost and 20,000 additional rides per day, respectively). Simply at the high prices and depression quantities on the upper part of the need curve, the percentage modify in quantity is relatively large, whereas the percentage change in cost is relatively small-scale. The absolute value of the price elasticity of need is thus relatively big. Every bit we move down the demand curve, equal changes in quantity represent smaller and smaller percent changes, whereas equal changes in price stand for larger and larger pct changes, and the absolute value of the elasticity measure declines. Between points C and D, for example, the price elasticity of demand is −1.00, and between points E and F the price elasticity of demand is −0.33.

On a linear need curve, the price elasticity of demand varies depending on the interval over which we are measuring it. For any linear need bend, the absolute value of the price elasticity of demand volition fall as we move down and to the right along the curve.

The Toll Elasticity of Demand and Changes in Full Revenue

Suppose the public transit authority is considering raising fares. Will its full revenues go upwardly or down? Total revenue is the price per unit times the number of units sold1. In this instance, information technology is the fare times the number of riders. The transit authorisation will certainly desire to know whether a price increase volition cause its total revenue to rising or fall. In fact, determining the touch on of a price change on total revenue is crucial to the analysis of many problems in economics.

We will do two quick calculations earlier generalizing the principle involved. Given the need curve shown in Figure five.2 "Price Elasticities of Demand for a Linear Demand Curve", nosotros see that at a price of $0.eighty, the transit authority will sell forty,000 rides per mean solar day. Full acquirement would be $32,000 per day ($0.80 times 40,000). If the price were lowered past $0.10 to $0.70, quantity demanded would increase to sixty,000 rides and total revenue would increase to $42,000 ($0.70 times sixty,000). The reduction in fare increases total revenue. Nonetheless, if the initial price had been $0.xxx and the transit dominance reduced it by $0.10 to $0.20, total revenue would decrease from $42,000 ($0.xxx times 140,000) to $32,000 ($0.xx times 160,000). And then it appears that the touch on of a price alter on total revenue depends on the initial price and, by implication, the original elasticity. We generalize this point in the remainder of this section.

The problem in assessing the impact of a price change on total acquirement of a adept or service is that a alter in price ever changes the quantity demanded in the contrary direction. An increase in price reduces the quantity demanded, and a reduction in cost increases the quantity demanded. The question is how much. Because full revenue is found past multiplying the price per unit times the quantity demanded, it is not articulate whether a change in price will cause total revenue to rising or fall.

Nosotros accept already fabricated this bespeak in the context of the transit potency. Consider the following three examples of cost increases for gasoline, pizza, and diet cola.

Suppose that 1,000 gallons of gasoline per twenty-four hour period are demanded at a price of $four.00 per gallon. Full revenue for gasoline thus equals $4,000 per day (=1,000 gallons per mean solar day times $iv.00 per gallon). If an increase in the toll of gasoline to $4.25 reduces the quantity demanded to 950 gallons per day, total revenue rises to $four,037.50 per day (=950 gallons per day times $4.25 per gallon). Even though people consume less gasoline at $4.25 than at $four.00, full acquirement rises because the college cost more makes upward for the driblet in consumption.

Next consider pizza. Suppose one,000 pizzas per week are demanded at a cost of $ix per pizza. Total revenue for pizza equals $9,000 per week (=one,000 pizzas per week times $ix per pizza). If an increment in the price of pizza to $10 per pizza reduces quantity demanded to 900 pizzas per calendar week, total revenue will yet be $9,000 per week (=900 pizzas per week times $10 per pizza). Again, when price goes upwards, consumers purchase less, only this time in that location is no change in total acquirement.

Now consider diet cola. Suppose 1,000 cans of nutrition cola per day are demanded at a price of $0.fifty per can. Total acquirement for nutrition cola equals $500 per day (=1,000 cans per day times $0.50 per can). If an increase in the price of diet cola to $0.55 per tin reduces quantity demanded to 880 cans per calendar month, full revenue for diet cola falls to $484 per day (=880 cans per day times $0.55 per can). As in the case of gasoline, people will buy less diet cola when the toll rises from $0.50 to $0.55, simply in this example total acquirement drops.

In our first case, an increase in price increased total acquirement. In the 2nd, a price increase left full revenue unchanged. In the third case, the price rise reduced full revenue. Is there a mode to predict how a price alter volition affect total revenue? There is; the effect depends on the price elasticity of demand.

Elastic, Unit Elastic, and Inelastic Demand

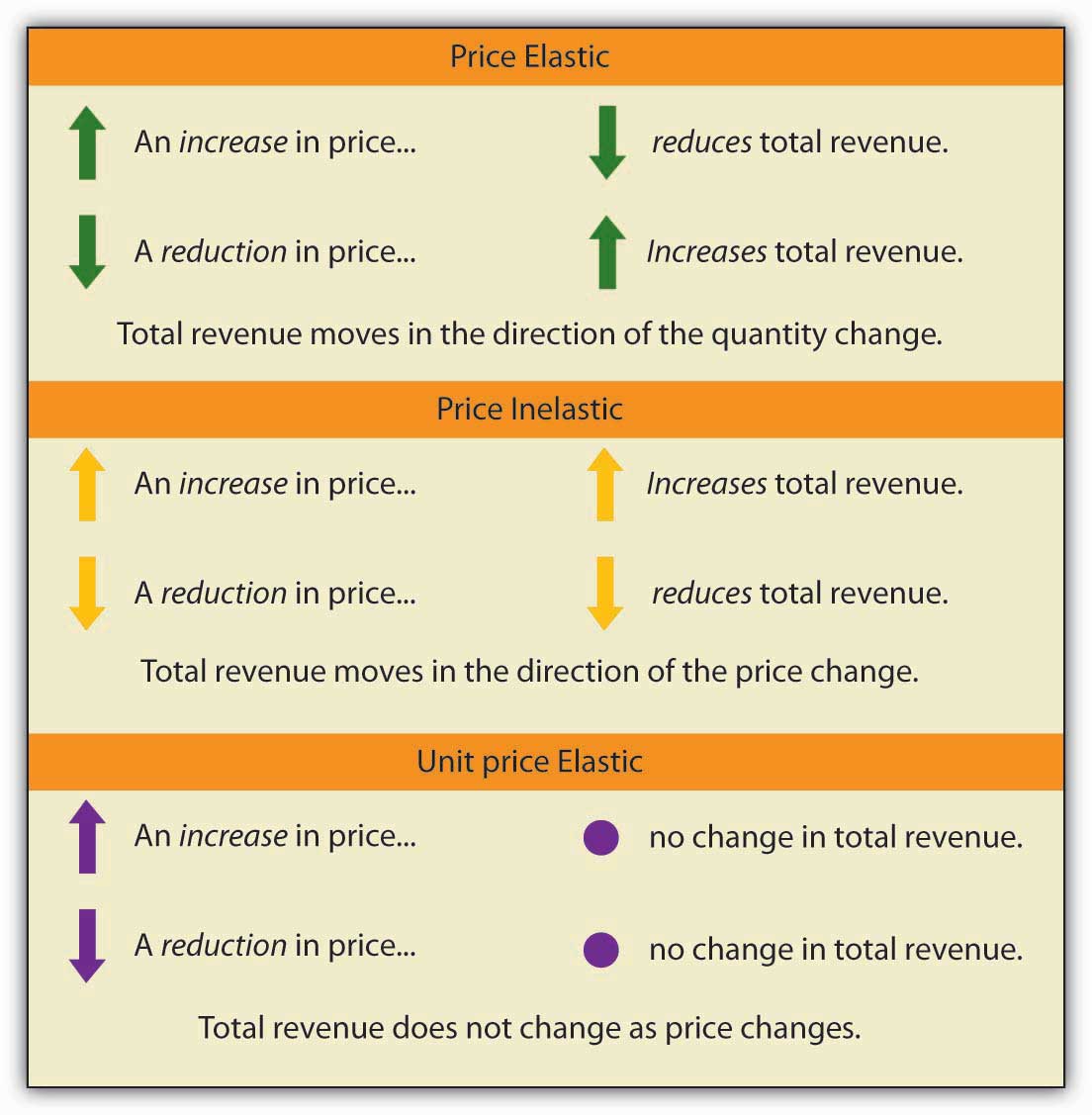

To make up one's mind how a toll change volition affect total revenue, economists place cost elasticities of demand in three categories, based on their accented value. If the accented value of the toll elasticity of demand is greater than ane, need is termed price elastic. If information technology is equal to 1, need is unit of measurement price rubberband. And if it is less than 1, need is price inelastic.

Relating Elasticity to Changes in Total Revenue

When the toll of a good or service changes, the quantity demanded changes in the reverse direction. Total revenue will motion in the management of the variable that changes by the larger percentage. If the variables move by the same percentage, full acquirement stays the same. If quantity demanded changes by a larger percentage than price (i.e., if demand is price elastic), total revenue will change in the direction of the quantity change. If price changes past a larger percent than quantity demanded (i.east., if demand is price inelastic), total revenue will motion in the management of the price change. If toll and quantity demanded change by the aforementioned percentage (i.e., if demand is unit price elastic), then total revenue does not modify.

When demand is price inelastic, a given percentage change in cost results in a smaller per centum modify in quantity demanded. That implies that total revenue volition move in the direction of the cost change: a reduction in cost will reduce total revenue, and an increase in toll will increase it.

Consider the cost elasticity of demand for gasoline. In the example above, 1,000 gallons of gasoline were purchased each day at a price of $4.00 per gallon; an increment in cost to $four.25 per gallon reduced the quantity demanded to 950 gallons per day. We thus had an average quantity of 975 gallons per twenty-four hours and an average price of $4.125. Nosotros tin thus calculate the arc price elasticity of demand for gasoline:

| Percentage change in quantity demanded = -50/975 = -5.1% |

| Percent alter in price=0.25/iv.125=6.06% |

| Price elasticity of need = -5.1%/half dozen.06% = -.084 |

The demand for gasoline is toll inelastic, and total revenue moves in the management of the cost change. When toll rises, total acquirement rises. Recall that in our instance above, total spending on gasoline (which equals total revenues to sellers) rose from $4,000 per twenty-four hour period (=i,000 gallons per day times $four.00) to $4037.fifty per solar day (=950 gallons per day times $4.25 per gallon).

When demand is price inelastic, a given pct modify in price results in a smaller percent change in quantity demanded. That implies that full revenue volition move in the direction of the price change: an increase in cost will increment full revenue, and a reduction in cost will reduce it.

Consider again the example of pizza that we examined above. At a toll of $nine per pizza, i,000 pizzas per week were demanded. Full revenue was $nine,000 per week (=i,000 pizzas per week times $9 per pizza). When the price rose to $ten, the quantity demanded cruel to 900 pizzas per week. Full revenue remained $nine,000 per week (=900 pizzas per week times $10 per pizza). Again, nosotros have an average quantity of 950 pizzas per week and an average price of $nine.fifty. Using the arc elasticity method, we can compute:

| Percentage change in quantity demanded = -100/950 = -10.5% |

| Pct change in cost = $1.00/$9.50 = x.v% |

| Cost elasticity of demand = -ten.5%/10.5% = -one.0 |

Demand is unit of measurement price rubberband, and full revenue remains unchanged. Quantity demanded falls by the aforementioned percentage past which price increases.

Consider next the instance of diet cola demand. At a price of $0.fifty per tin, 1,000 cans of diet cola were purchased each solar day. Total revenue was thus $500 per twenty-four hour period (=$0.50 per can times 1,000 cans per twenty-four hours). An increase in cost to $0.55 reduced the quantity demanded to 880 cans per twenty-four hours. Nosotros thus have an average quantity of 940 cans per day and an average toll of $0.525 per tin can. Calculating the price elasticity of demand for diet cola in this case, we have:

| Percentage alter in quantity demanded = -120/940 = -12.8% |

| Per centum change in price = $0.05/$0.525 = ix.5% |

| Price elasticity of need = -12.8%/9.five% = -one.3 |

The demand for diet cola is price elastic, so total revenue moves in the direction of the quantity change. It falls from $500 per solar day before the price increase to $484 per day after the toll increase.

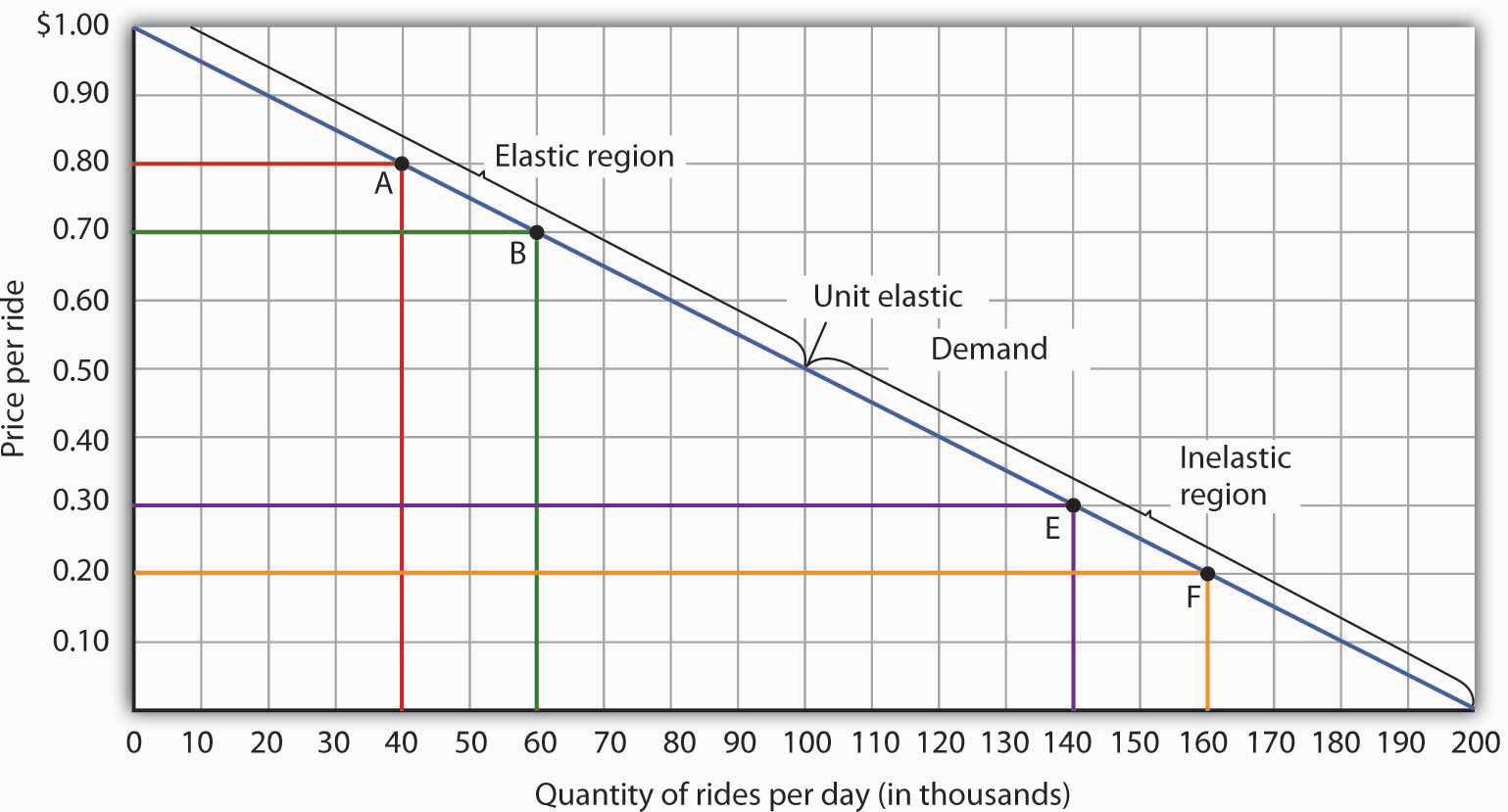

A demand bend can besides exist used to prove changes in total revenue. Figure 5.3 "Changes in Total Revenue and a Linear Need Bend" shows the demand curve from Figure v.1 "Responsiveness and Need" and Figure 5.2 "Price Elasticities of Demand for a Linear Demand Curve". At point A, total acquirement from public transit rides is given by the area of a rectangle drawn with point A in the upper right-mitt corner and the origin in the lower left-mitt corner. The height of the rectangle is toll; its width is quantity. We have already seen that total revenue at point A is $32,000 ($0.80 × xl,000). When we reduce the toll and movement to signal B, the rectangle showing full acquirement becomes shorter and wider. Notice that the area gained in moving to the rectangle at B is greater than the surface area lost; total revenue rises to $42,000 ($0.70 × 60,000). Call up from Effigy 5.2 "Toll Elasticities of Demand for a Linear Demand Curve" that demand is elastic betwixt points A and B. In general, demand is elastic in the upper half of any linear demand curve, so full revenue moves in the direction of the quantity change.

Figure 5.three Changes in Total Acquirement and a Linear Need Curve

Moving from bespeak A to point B implies a reduction in price and an increase in the quantity demanded. Demand is elastic betwixt these 2 points. Full revenue, shown by the areas of the rectangles drawn from points A and B to the origin, rises. When we motility from point East to bespeak F, which is in the inelastic region of the demand curve, total revenue falls.

A move from point E to point F besides shows a reduction in cost and an increase in quantity demanded. This time, however, we are in an inelastic region of the demand bend. Total revenue now moves in the direction of the price change—it falls. Notice that the rectangle drawn from betoken F is smaller in expanse than the rectangle drawn from point Eastward, once over again confirming our earlier adding.

Figure v.4

We have noted that a linear demand curve is more elastic where prices are relatively loftier and quantities relatively low and less rubberband where prices are relatively depression and quantities relatively high. We can be even more than specific. For whatsoever linear demand curve, demand will be price elastic in the upper half of the curve and price inelastic in its lower half. At the midpoint of a linear need curve, demand is unit cost rubberband.

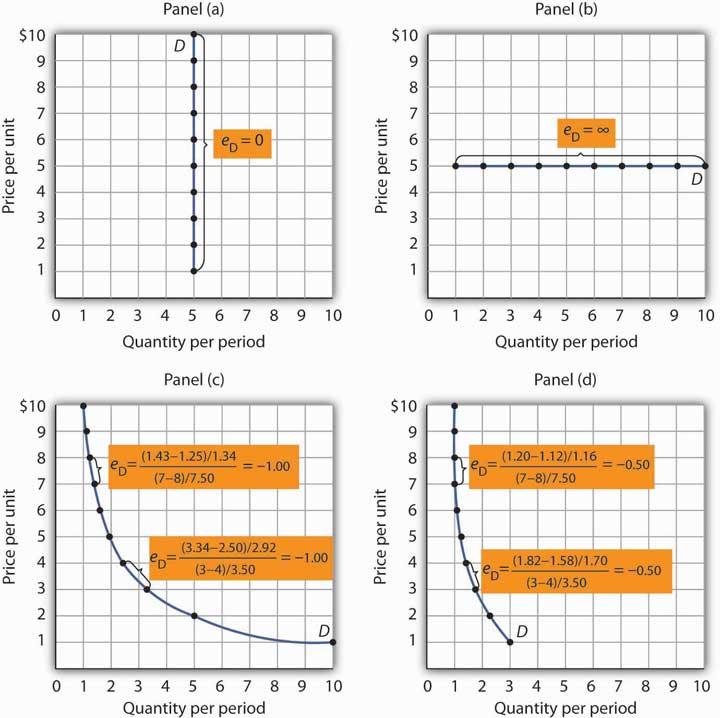

Constant Price Elasticity of Demand Curves

Effigy 5.5 "Demand Curves with Constant Price Elasticities" shows four demand curves over which price elasticity of demand is the same at all points. The demand curve in Panel (a) is vertical. This ways that toll changes accept no consequence on quantity demanded. The numerator of the formula given in Equation 5.two for the toll elasticity of demand (percent alter in quantity demanded) is zero. The cost elasticity of need in this case is therefore nil, and the need curve is said to be perfectly inelastic. This is a theoretically extreme case, and no good that has been studied empirically exactly fits information technology. A expert that comes shut, at to the lowest degree over a specific price range, is insulin. A diabetic will not consume more insulin equally its price falls but, over some price range, will consume the amount needed to control the disease.

Figure 5.5 Need Curves with Abiding Toll Elasticities

The demand curve in Panel (a) is perfectly inelastic. The demand curve in Panel (b) is perfectly elastic. Price elasticity of demand is −1.00 all along the demand curve in Panel (c), whereas it is −0.fifty all forth the need curve in Console (d).

As illustrated in Figure 5.5 "Demand Curves with Constant Toll Elasticities", several other types of demand curves have the same elasticity at every point on them. The demand curve in Panel (b) is horizontal. This means that fifty-fifty the smallest price changes accept enormous effects on quantity demanded. The denominator of the formula given in Equation 5.2 for the cost elasticity of demand (percentage modify in price) approaches nil. The price elasticity of demand in this example is therefore infinite, and the need curve is said to be perfectly elastic. This is the type of need curve faced past producers of standardized products such as wheat. If the wheat of other farms is selling at $4 per bushel, a typical farm can sell as much wheat as it wants to at $four simply nothing at a higher price and would have no reason to offer its wheat at a lower price.

The nonlinear demand curves in Panels (c) and (d) have price elasticities of demand that are negative; but, unlike the linear demand curve discussed above, the value of the price elasticity is constant all along each demand bend. The demand curve in Panel (c) has toll elasticity of demand equal to −1.00 throughout its range; in Panel (d) the price elasticity of demand is equal to −0.50 throughout its range. Empirical estimates of need often evidence curves similar those in Panels (c) and (d) that have the same elasticity at every bespeak on the curve.

Heads Up!

Exercise not misfile price inelastic demand and perfectly inelastic need. Perfectly inelastic demand ways that the change in quantity is nil for any percentage modify in price; the demand curve in this case is vertical. Price inelastic demand means but that the percentage change in quantity is less than the percent change in toll, not that the alter in quantity is nothing. With price inelastic (as opposed to perfectly inelastic) demand, the demand curve itself is still downward sloping.

Determinants of the Price Elasticity of Demand

The greater the accented value of the price elasticity of need, the greater the responsiveness of quantity demanded to a price change. What determines whether need is more or less price rubberband? The about important determinants of the price elasticity of demand for a practiced or service are the availability of substitutes, the importance of the item in household budgets, and time.

Availability of Substitutes

The price elasticity of need for a good or service will be greater in accented value if many shut substitutes are available for it. If there are lots of substitutes for a particular adept or service, then information technology is piece of cake for consumers to switch to those substitutes when there is a toll increase for that good or service. Suppose, for instance, that the price of Ford automobiles goes up. There are many close substitutes for Fords—Chevrolets, Chryslers, Toyotas, and so on. The availability of close substitutes tends to make the demand for Fords more price elastic.

If a good has no close substitutes, its demand is likely to be somewhat less price elastic. At that place are no close substitutes for gasoline, for example. The cost elasticity of need for gasoline in the intermediate term of, say, three–9 months is generally estimated to be about −0.five. Since the accented value of price elasticity is less than 1, it is toll inelastic. We would await, though, that the demand for a particular brand of gasoline will be much more than price elastic than the need for gasoline in general.

Importance in Household Budgets

I reason cost changes affect quantity demanded is that they alter how much a consumer tin can buy; a alter in the price of a good or service affects the purchasing ability of a consumer's income and thus affects the amount of a good the consumer will buy. This effect is stronger when a good or service is of import in a typical household's budget.

A alter in the price of jeans, for example, is probably more than of import in your budget than a change in the price of pencils. Suppose the prices of both were to double. You had planned to purchase four pairs of jeans this year, simply now you might determine to make exercise with ii new pairs. A modify in pencil prices, in contrast, might lead to very little reduction in quantity demanded simply because pencils are not likely to loom large in household budgets. The greater the importance of an item in household budgets, the greater the absolute value of the toll elasticity of demand is likely to be.

Time

Suppose the price of electricity rises tomorrow morning. What will happen to the quantity demanded?

The answer depends in large part on how much time we allow for a response. If we are interested in the reduction in quantity demanded past tomorrow afternoon, we tin expect that the response will be very small. But if we give consumers a year to reply to the price change, we tin can expect the response to be much greater. Nosotros expect that the absolute value of the price elasticity of demand will exist greater when more time is immune for consumer responses.

Consider the price elasticity of crude oil demand. Economist John C. B. Cooper estimated short- and long-run price elasticities of demand for rough oil for 23 industrialized nations for the period 1971–2000. Professor Cooper plant that for virtually every state, the price elasticities were negative, and the long-run price elasticities were by and large much greater (in absolute value) than were the short-run price elasticities. His results are reported in Table 5.1 "Short- and Long-Run Price Elasticities of the Demand for Crude Oil in 23 Countries". As you can see, the research was reported in a journal published by OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries), an organization whose members take profited greatly from the inelasticity of demand for their product. By restricting supply, OPEC, which produces nigh 45% of the world's crude oil, is able to put upwardly force per unit area on the cost of crude. That increases OPEC'south (and all other oil producers') total revenues and reduces total costs.

Table 5.1 Brusk- and Long-Run Price Elasticities of the Demand for Crude Oil in 23 Countries

| Country | Brusque-Run Toll Elasticity of Demand | Long-Run Price Elasticity of Need |

|---|---|---|

| Australia | −0.034 | −0.068 |

| Austria | −0.059 | −0.092 |

| Canada | −0.041 | −0.352 |

| Mainland china | 0.001 | 0.005 |

| Kingdom of denmark | −0.026 | −0.191 |

| Finland | −0.016 | −0.033 |

| France | −0.069 | −0.568 |

| Germany | −0.024 | −0.279 |

| Greece | −0.055 | −0.126 |

| Iceland | −0.109 | −0.452 |

| Ireland | −0.082 | −0.196 |

| Italian republic | −0.035 | −0.208 |

| Japan | −0.071 | −0.357 |

| Korea | −0.094 | −0.178 |

| Netherlands | −0.057 | −0.244 |

| New Zealand | −0.054 | −0.326 |

| Norway | −0.026 | −0.036 |

| Portugal | 0.023 | 0.038 |

| Spain | −0.087 | −0.146 |

| Sweden | −0.043 | −0.289 |

| Switzerland | −0.030 | −0.056 |

| United Kingdom | −0.068 | −0.182 |

| Us | −0.061 | −0.453 |

For most countries, price elasticity of demand for crude oil tends to be greater (in accented value) in the long run than in the short run.

Source: John C. B. Cooper, "Cost Elasticity of Demand for Rough Oil: Estimates from 23 Countries," OPEC Review: Energy Economics & Related Issues, 27:1 (March 2003): 4. The estimates are based on information for the period 1971–2000, except for China and Republic of korea, where the period is 1979–2000. While the price elasticities for Prc and Portugal were positive, they were not statistically meaning.

Cardinal Takeaways

- The price elasticity of demand measures the responsiveness of quantity demanded to changes in price; it is calculated by dividing the pct change in quantity demanded past the percentage change in price.

- Demand is price inelastic if the absolute value of the price elasticity of demand is less than 1; it is unit price rubberband if the accented value is equal to 1; and it is price rubberband if the absolute value is greater than 1.

- Need is price rubberband in the upper half of whatever linear demand bend and toll inelastic in the lower one-half. It is unit price elastic at the midpoint.

- When need is price inelastic, total revenue moves in the direction of a price change. When need is unit price elastic, total acquirement does non change in response to a price change. When need is price elastic, total revenue moves in the management of a quantity modify.

- The absolute value of the price elasticity of demand is greater when substitutes are bachelor, when the skillful is important in household budgets, and when buyers have more time to adjust to changes in the cost of the proficient.

Attempt It!

You are now ready to play the part of the manager of the public transit system. Your finance officer has just advised yous that the system faces a deficit. Your board does not desire you to cutting service, which means that y'all cannot cut costs. Your merely hope is to increase acquirement. Would a fare increase boost acquirement?

You consult the economist on your staff who has researched studies on public transportation elasticities. She reports that the estimated price elasticity of need for the outset few months after a price alter is about −0.iii, simply that after several years, information technology will exist about −1.five.

- Explain why the estimated values for toll elasticity of need differ.

- Compute what will happen to ridership and revenue over the adjacent few months if y'all determine to enhance fares past 5%.

- Compute what volition happen to ridership and acquirement over the next few years if you decide to raise fares by five%.

- What happens to total revenue at present and afterward several years if yous choose to raise fares?

Instance in Bespeak: Elasticity and Finish Lights

Figure 5.6

We all face the state of affairs every day. You are approaching an intersection. The yellow light comes on. You lot know that you are supposed to slow downward, but you are in a fleck of a hurry. And then, you speed upward a trivial to try to make the calorie-free. But the ruby-red light flashes on just before you get to the intersection. Should y'all risk information technology and go through?

Many people faced with that situation accept the risky choice. In 1998, 2,000 people in the Usa died every bit a result of drivers running red lights at intersections. In an attempt to reduce the number of drivers who make such choices, many areas have installed cameras at intersections. Drivers who run red lights have their pictures taken and receive citations in the postal service. This enforcement method, together with recent increases in the fines for driving through red lights at intersections, has led to an intriguing application of the concept of elasticity. Economists Avner Bar-Ilan of the Academy of Haifa in State of israel and Bruce Sacerdote of Dartmouth Academy have estimated what is, in effect, the cost elasticity for driving through stoplights with respect to traffic fines at intersections in Israel and in San Francisco.

In December 1996, Israel sharply increased the fine for driving through a cherry-red low-cal. The quondam fine of 400 shekels (this was equal at that time to $122 in the Usa) was increased to 1,000 shekels ($305). In Jan 1998, California raised its fine for the crime from $104 to $271. The land of Israel and the city of San Francisco installed cameras at several intersections. Drivers who ignored stoplights got their pictures taken and automatically received citations imposing the new higher fines.

We tin can think of driving through carmine lights as an action for which there is a demand—after all, ignoring a ruby-red light speeds up one'due south trip. It may besides generate satisfaction to people who savour disobeying traffic laws. The concept of elasticity gives us a way to bear witness only how responsive drivers were to the increase in fines.

Professors Bar-Ilan and Sacerdote obtained information on all the drivers cited at 73 intersections in Israel and 8 intersections in San Francisco. For Israel, for instance, they defined the period January 1992 to June 1996 as the "earlier" period. They compared the number of violations during the before menstruum to the number of violations from July 1996 to December 1999—the "after" flow—and constitute at that place was a reduction in tickets per commuter of 31.5 per cent. Specifically, the average number of tickets per driver was 0.073 during the period before the increase; information technology fell to 0.050 after the increase. The increment in the fine was 150 per cent. (Note that, because they were making a "earlier" and "after" calculation, the authors used the standard method described in the Heads Up! on computing a percentage alter—i.east., they computed the per centum changes in comparing to the original values instead of the average value of the variables.) The elasticity of citations with respect to the fine was thus −0.21 (= −31.5%/150%).

The economists estimated elasticities for item groups of people. For example, young people (age 17–30) had an elasticity of −0.36; people over the age of xxx had an elasticity of −0.sixteen. In general, elasticities vicious in absolute value as income rose. For San Francisco and Israel combined, the elasticity was betwixt −0.26 and −0.33.

In general, the results showed that people responded rationally to the increases in fines. Increasing the price of a particular behavior reduced the frequency of that behavior. The study also points out the effectiveness of cameras as an enforcement technique. With cameras, violators tin be sure they will be cited if they ignore a red light. And reducing the number of people running red lights clearly saves lives.

Source: Avner Bar-Ilan and Bruce Sacerdote. "The Response of Criminals and Non-Criminals to Fines." Periodical of Constabulary and Economic science, 47:1 (April 2004): one–17.

Answers to Try Information technology! Problems

- The absolute value of cost elasticity of demand tends to be greater when more than fourth dimension is allowed for consumers to answer. Over fourth dimension, riders of the commuter rail system tin can organize automobile pools, motility, or otherwise suit to the fare increment.

- Using the formula for price elasticity of need and plugging in values for the gauge of price elasticity (−0.5) and the percentage modify in price (5%) and and so rearranging terms, we can solve for the percent change in quantity demanded as: east D = %Δ in Q/%Δ in P ; −0.5 = %Δ in Q/five% ; (−0.five)(5%) = %Δ in Q = −2.5%. Ridership falls past 2.5% in the showtime few months.

- Using the formula for price elasticity of demand and plugging in values for the estimate of price elasticity over a few years (−i.five) and the pct change in cost (v%), we can solve for the percentage change in quantity demanded as e D = %Δ in Q/%Δ in P ; −1.5 = %Δ in Q/v% ; (−i.five)(5%) = %Δ in Q = −7.5%. Ridership falls by 7.5% over a few years.

- Full acquirement rises immediately after the fare increase, since demand over the immediate flow is cost inelastic. Total revenue falls later on a few years, since demand changes and becomes toll elastic.

iObserve that since the number of units sold of a good is the same as the number of units bought, the definition for total acquirement could also be used to define full spending. Which term we use depends on the question at hand. If we are trying to determine what happens to revenues of sellers, then we are asking about full revenue. If we are trying to determine how much consumers spend, then we are asking nigh full spending.

2Division by cypher results in an undefined solution. Saying that the price elasticity of demand is infinite requires that we say the denominator "approaches" goose egg.

bernsteinwitheauted.blogspot.com

Source: https://open.lib.umn.edu/principleseconomics/chapter/5-1-the-price-elasticity-of-demand/

0 Response to "If the Price of a Good Rises, What Are People Likely to Do?"

Post a Comment